I was recently watching Facebook's F8 conference - which was streamed on Facebook Live - and it got me curious as to how Facebook Live scales so seamlessly to millions of people around the world.

How does Facebook Live scale? Let's dig in and analyze!

The Challenges

Before analyzing the architecture and how Facebook Live can scale to that extent, let's look at some of the challenges that building such a product comes with.

Chris Cox, the company's Chief Product Officer, had an interview with Wired[1] back in April of 2016, where he enumerated the following challenges, considering that there were over 1.86 billion monthly active users on Facebook by the end of 2016:

- Needs to be able to serve up millions of simultaneous streams

- Needs to be able to support millions of users on the same stream

To quote Chris Cox, this "turns out it’s a really hard infrastructure problem", which makes it even more exciting to deconstruct and analyze.

Another unique challenge with live video is that traffic comes in spikes, and your infrastructure must be able to handle huge traffic spikes. For instance, when a celebrity starts a live video stream, there will be a huge traffic spike when users join and while the video is still streaming live, and then it'll slow down drastically when the video ends but it will still by viewable by users, even if it is no longer streaming live. The main challenge will be to gracefully handle the spikes while it's streaming live.

The Architecture

For the purpose of this article, I'll be exclusively focusing on the high traffic spikes that occur when a user with millions of followers (e.g. a celebrity) starts a live broadcast. In cases like this, more than a million people could be watching the broadcast at the same time, and when they all join around the same time, this causes major stress on the servers and infrastructure.

When all these requests come in at once - which is called the thundering herd problem[2] - it can cause streaming issues such as lag, dropped packets, or even preventing users from joining the broadcast.

When there's a possibility you may run into such a problem, the first thing you should do is prevent all the requests from hitting your streaming server directly, which could be fatal and drop the server all together. Instead, you should aim at adding multiple layers that will filter these requests and ensure that only the necessary requests make it to the streaming server.

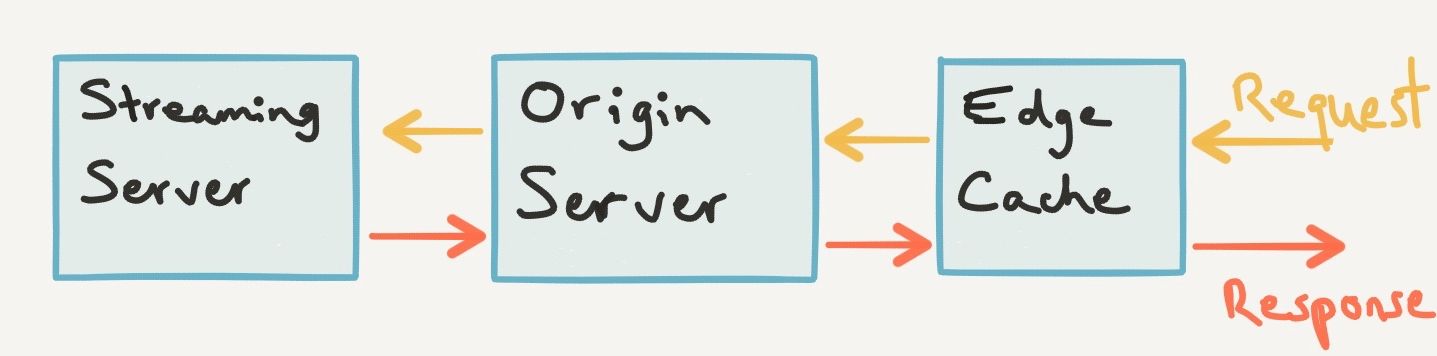

This can be achieved in many different ways, depending on the size of your product and the number of users. In Facebook's case, they chose the following architecture:

It's important to note here that Edge Cache servers are spread out across the globe to support Facebook's global reach. There's also a one-to-many relationship between the Origin Server and the Edge Cache, where multiple Edge Cache servers can send requests to the same Origin Server.

The flow works as follow:

1- The requests first hit the Edge Cache server closest to the user in order to reduce the latency between the user and the server. The Edge Cache servers are essentially a cache layer and do not do much processing.

2- If the requested packets are in the Edge Cache, then they are returned to the user.

3- If they are not in the Edge Cache, then the request is forwarded to the Origin Server, which is another cache server and has a similar architecture to the Edge Cache server.

4- If the requested packets are in the Origin Server, then they are returned to the Edge Cache who caches them before returning them to the user.

5- If they are not in the Origin Server, then the request is forwarded to the specific Streaming Server handling that live broadcast. The Streaming Server then returns the packets to the Origin Server, who caches them before returning them to the Edge Cache. The Edge Cache caches the response and returns the packets to the user.

6- Future requests for the same packets will then simply be handled by the Edge Cache and will not travel further than that layer, which speeds up the process incredibly and reduces the load on the Streaming Server.

As we can see, this architecture greatly reduces the number of requests that make it to the Streaming Server. For instance, if 5 requests make it to the Edge Cache sequentially, only the first one will go all the way to the Streaming Server and back, while the 4 others will immediately get a response from Edge Cache since it'll have cached it already.

However, this is still not enough for Facebook's reach. In fact, according to an article released by Facebook[3], this architecture still leaks about 1.8% of requests to the Streaming Server. At their scale, with millions of requests, 1.8% is a huge amount to leak and puts a lot of stress on the Streaming Server.

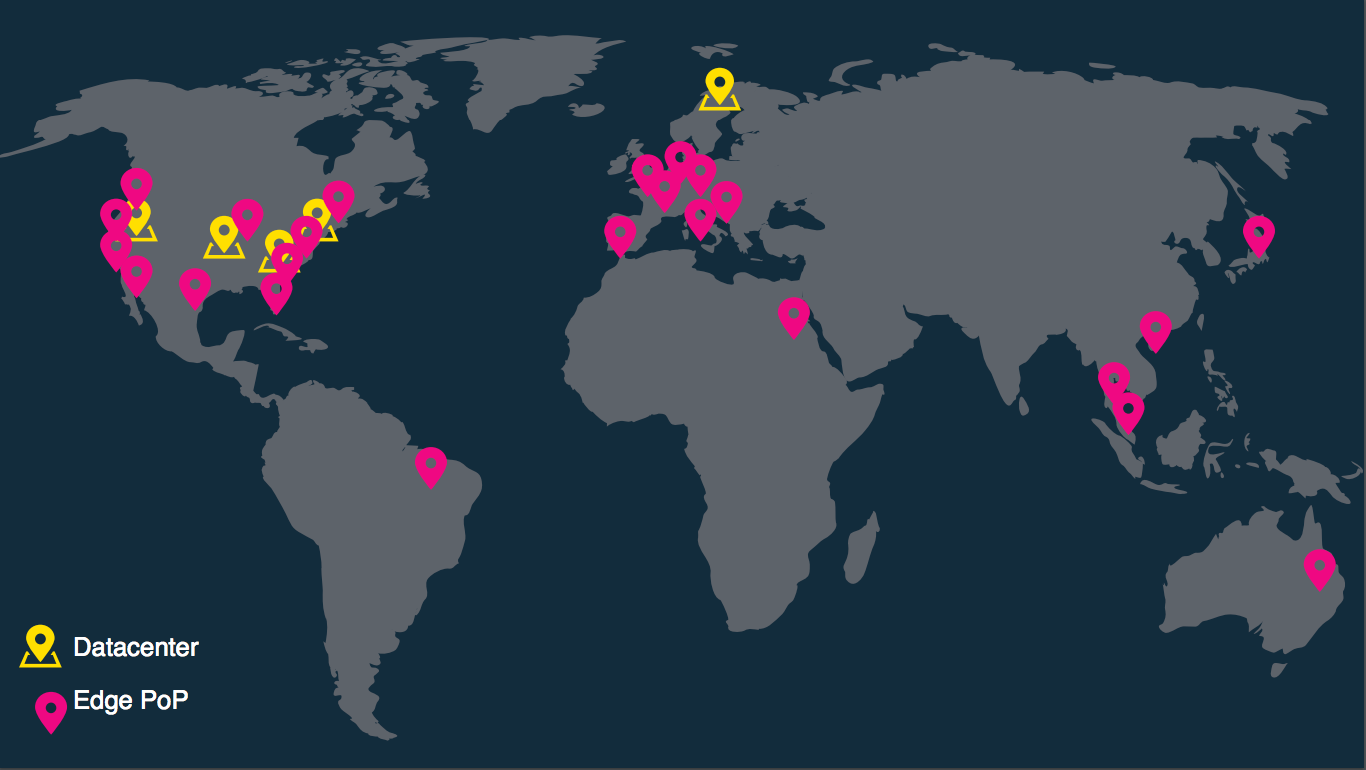

Facebook's Global Reach: Edge Cache servers are in pink, and Origin Servers are in yellow. Source: http://cs.unc.edu/xcms/wpfiles/50th-symp/Moorthy.pdf

Why is it Leaking so many Requests?

The first flaw in the architecture above is that simultaneous requests to the same Edge Cache will make it through to the Origin Server. Since the Edge Cache forwards all requests for missing packets to the next layer, if simultaneous requests ask for packet A and it is not in the cache, all those requests will be forwarded. Extrapolating this at Facebook's scale, we can quickly see how so many requests are leaked.

The second flaw in the architecture is that multiple Edge Cache boxes can send the same packet request to the Origin Server, which will in turn forward all those simultaneous requests to the Streaming Server since the packet is not in its cache. This is similar to the first flaw but it's happening at the Origin Server level.

Again, 1.8% may not seem like a lot for normal products, but at Facebook's scale, it is indeed an important issue that needs to be resolved.

Adjusting the Architecture for High Scaling

Facebook's solution to this problem is creative, yet simple to understand. When multiple requests for the same packet hit the Edge Cache, they are grouped together in a request queue and only one goes through to the Origin Server. This is called request coalescing. Once the response comes from the server, it is stored in the cache and then the requests in the queue are responded from the cache.

For instance, when 10 simultaneous requests make it to the Edge Cache, they are all added to the same request queue and only one goes through, which helps reduce the leaking of requests. If we compare this scenario to the original setup, where all 10 simultaneous requests would have made it through, we see a huge increase in performance.

The same concept was also applied at the Origin Server level, where all requests for the same packet - coming from one or many Edge Cache endpoints - are grouped together and only one of them makes it through to the Streaming Server. Needless to say that this greatly reduces the overhead on the Streaming Server, especially consider the amount of requests a live broadcast may receive.

Load Balancing

Another important tweak that Facebook implemented was load balancing for the Edge Cache servers. In some cases, with huge traffic spikes, Edge Cache servers can get overloaded and no longer perform consistently, despite the use of request coalescing. To avoid such situations, the load balancer redirects requests to the closest Edge Cache with availability for the request. For instance, if the Edge Cache closest to you is already serving 200 000 requests, then the load balancer might forward you to an Edge Cache a little further but that is serving half the number of requests, which would mean you would still be getting a response much faster.

Facebook determines which Edge Cache is available by constantly measuring the load on these servers and keeping track of its performance. It goes even further than that and uses an algorithm to predict the load before it happens, which is incredible. The basis of the algorithm is complex enough that it would require its own article so I will not be getting into that at the moment, but it is a very interesting topic that I may cover in the near future.

Request Coalescing Using Nginx

For those of you using Nginx, request coalescing can be enabled by setting the proxy_cache_lock config to on (default value is off), as explained in the docs here:

When enabled, only one request at a time will be allowed to populate a new cache element identified according to the

proxy_cache_keydirective by passing a request to a proxied server. Other requests of the same cache element will either wait for a response to appear in the cache or the cache lock for this element to be released, up to the time set by the proxy_cache_lock_timeout directive.

Conclusion

I had a lot of fun researching and dissecting Facebook Live's architecture and how the engineers were able to make the product scale to millions of users. Although we may never build products that reach such a high amount of users, there are great lessons here that we can use in our own products, such as how adding multiple layers in the architecture helps filtering the number of requests that make it through to the processing server. This, in turn, improves the performance and availability of the server, which provides a better product to users and helps scaling it.

Footnotes

Credits

- Scaling Facebook Live at @Scale Conference

- Scaling Facebook Live (2) at @Scale Conference